Have you ever heard of Freedman’s Savings and Loan? If not, unfortunately, you’re not alone. The Freedman Savings and Trust Company was a private corporation chartered by an act of the United States government signed in 1865 by President Abraham Lincoln. It was created to help the newly freed African-Americans as they endeavored to become financially stable. By June of 1874, it was closed. Here’s how that legacy is still with us today.

About Freedman’s Bank:

Why a 19th-century bank failure still matters

The Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company and African American Genealogical Research

Transcript:

Welcome to the premiere of The Deep Cut, a power up from Founder Hustle, the podcast series by, for, and about the new majority entrepreneur. I’m your host, Melissa Bradley, founder of 1863 Ventures.

Through interviews with entrepreneurs, Founder Hustle provides practical advice and tools to entrepreneurs and allows for their family, investors, and community to learn of the highs and lows of launching and running a successful and scalable business.

But as a seasoned venture capitalist, I know that you can’t be successful without knowing what has come before, as well as preparing for what is yet to come. And that’s where The Deep Cut comes in.

These bonus episodes are where we level up on the history that brought us to this moment and the current events that can impact the stability and growth of your business and shape your future on your journey from founder to CEO

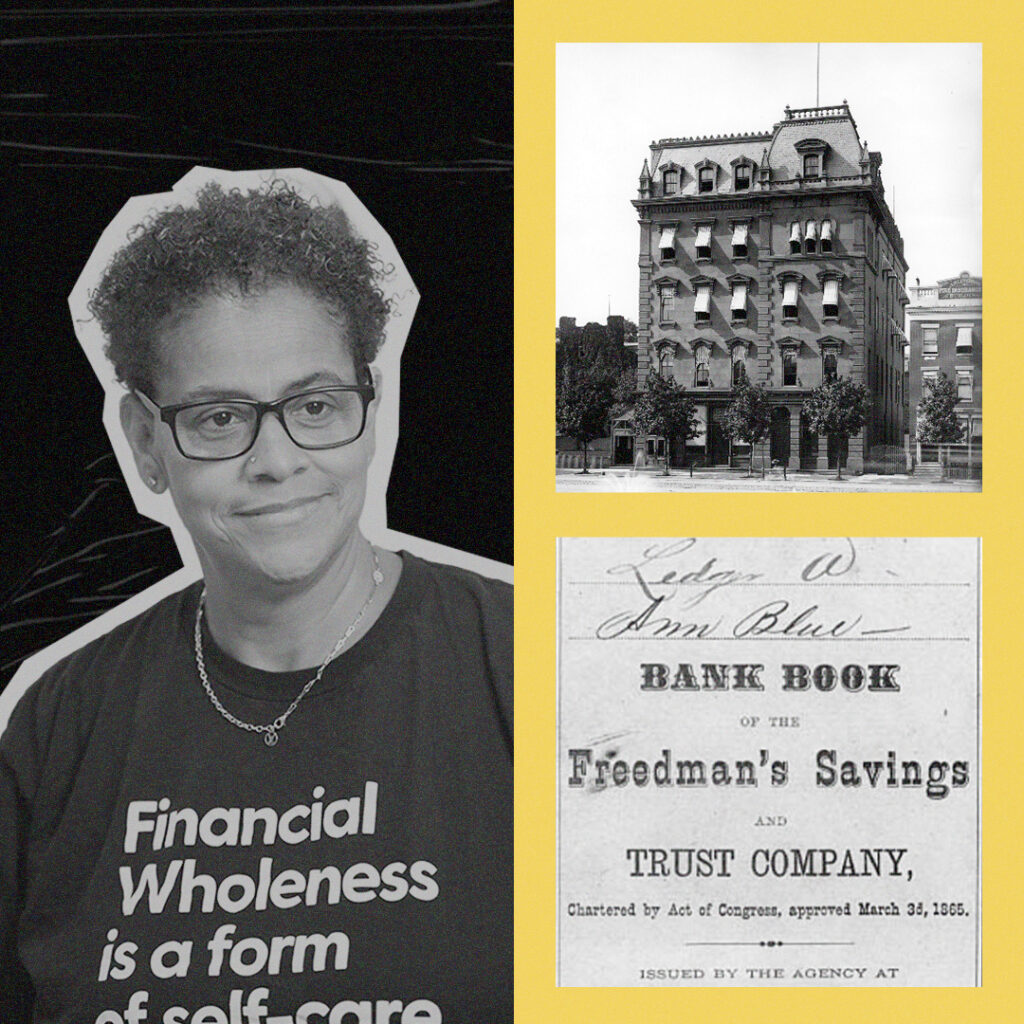

In the premiere episode of Founder Hustle – the episode with Chris Denson, host of the Innovation Crush podcast – we briefly talked about Freedman’s Bank. But I thought it imperative to give more context about the Freedman’s Savings Bank, or what was officially known as the Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company, since it was not only an important part of the foundation of the banking industry, but also important to the history of Black people in America.

Have you ever heard of Freedman’s Savings and Loan? If not, unfortunately, you’re not alone. Today, there are 143 Federal Deposit Insurance company recognized minority banks serving new majority communities across the United States. Just 20 of these institutions though are led by black CEOs. Although most minority banks operate in metropolitan areas, they’re also located in rural and suburban areas across the United States. Now, you may say, “Well, 143, that’s a lot.” Well, over a hundred and more than you and I could probably name, [chuckle] it represents a fraction of what used to be. Black-owned banks flourished in the ’50s and ’60s, but from 2001 to 2018, the number of black-owned financial institutions declined over 50%. Today, that number is down another 9% leaving only 21 black-owned banks in the United States. Until 2021 not one of those banks manage assets over a billion dollars, except in July of 2021, we had something to celebrate.

City First Bank and Broadway Financial, an institution that ironically I used to regulate when I was part of the Treasury Department, merged to become City First Broadway. The newly merged Bank has more than one billion dollars in combined assets and is now the largest black-owned minority depository institution in the United States. Hallelujah. Now, let’s not get it twisted. City First Broadway is not unique. Rather, it is the manifestation of what should have been after the creation of the first bank for African-Americans over 150 years ago. That’s right, 150 years. The Freedman Savings and Trust Company was a private corporation chartered by an act of the United States government signed in 1865 by President Abraham Lincoln. It was created to help the newly freed African-Americans as they endeavor to become financially stable.

Originally, the bank was headquartered in New York, where we know all great things happen, but later moved to Washington DC. Eventually, there were more than 37 locations across 17 states. With the passage of the 13th Amendment in the end of the Civil War in 1865, as we know, slavery was finally abolished in the United States. After all those years, almost overnight, nearly four million African-American men, women and children, were free. Within the South and ruins they faced disorder and danger. Most of them had no home, no money, no work, and their relatives were scattered all over the United States and almost impossible to find. To address the needs of the newly freed slaves, and believe it or not, the United States government created the Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen and Abandoned Lands, commonly known as the Freedman’s Bureau. Now, this agency provided food, housing, and medical aid to tens of thousands of freed slaves. It located relatives and reunited families, and it even helped to establish schools all across the south, which we know later were boycotted and picketed for African-Americans.

Meanwhile, a group of missionaries, abolitionists and businessmen, saw that African-Americans would need support and education to become financially secure. The group worked to create a savings bank for former slaves, African-American veterans and their families. And believe it or not, in 1865, they succeeded. The Freedman’s Savings Trust and Company, also called the Freedman’s bank opened for business in New York on April 4th, 1865. At first, it was very successful, surprise, surprise. Branches were soon opened in cities with large African-American populations, mostly in the south. Within a few years, the bank had 19 branches and 23,000 depositors, almost all were African-Americans. Many African-American churches and institutions such as Howard University had accounts there. Ultimately, 37 branches were established and over 100,000 people opened accounts.

Now, deposits at the bank were small, less than $60, because people could open an account with this little as five cents and accounts with at least $1 earned interest, those were the days. People would often put their money in the bank during the summer and autumn and take it out in the winter and spring when their supplies would be running low. People also use their savings to buy bigger items, such as homes, land, farm animals and tools. African-Americans, thank God, were also hired to work at the bank. By 1874, nearly half of the bank employees were at African-American, most were cashiers who were deemed to be the top officials at the branches, others were assistant cashiers, clerks, or messengers. Even though the Freedman’s bank business grew, it struggled financially.

Maintaining so many branches was costly and the bank’s source of income was small. It made a profit by investing depositors’ money in government bonds, but these bonds didn’t pay a huge rate of interest, no different than we experience today. The Freedman’s bank survived with the help of the Freedmen’s Bureau. In fact, in 1867, the Freedman’s Bank moved its headquarters from New York City to Washington DC. Soon after, a group of local bankers, politicians and businessmen began to take control. Now you can only guess what happened next. At the urging of the new trustees, Congress amended the bank’s charter. The trustees now began to invest in real estate projects and railroads and they made risky loans to friends, some with no collateral. Now isn’t this a story we’ve already heard? Some of the trustees were in charge of other banks as well, and when they made bad loans at their banks, they transferred the bad loans to where? You named it, Freedman’s Bank. As Frederick Douglass, a famous writer and speaker, widely respected in the African-American community would later describe it, the bank became the black man’s cow, but the white man’s milk.

When a financial panic hit the country in 1873, most of the Freedman’s bank investments lost value and became worthless. Of course, the bank was nearly doomed after that. Several branches thereafter were hit by bank runs during which crowds of depositors demanded their money. The branches met demands, but the cash reserves of Freedman’s Bank were drained and a number of trustees finally resigned. In the meantime, no one had been watching what the trustees were doing, sounds familiar?

The United States Congress was supposed to supervise the Freedman’s bank, but paid little attention. When Congress finally sent the Comptroller of the Currency to look at the bank books, it was unfortunately too late. In an attempt to save the bank, the trustees, asked Frederick Douglass to replace the bank president John Alford. He accepted the position, not knowing how bad the situation was. Isn’t that always the case? He soon realized he was “married to a corpse.” Six weeks after taking the job, he told Congress to shut the bank down. The trustees fought the closing at first, but they soon realized that the bank could not be saved.

In June 1874, the Freedman’s bank was closed. According to some historians, the failure of the Freedman’s bank created a deep distrust of banks in the African-American community. The bank’s failure was a tremendous blow as most individuals lost every penny they had saved, but more importantly, African-Americans had taken pride in the bank. At a time when people were saying ex-slaves could not make it on their own, freedman’s bank was one piece of evidence to prove that they were wrong, and that African-Americans could indeed make it on their own. Ministers, community leaders, and teachers had worked so hard to convince the communities to trust the bank. I share this story as another example of how our greatness has been suppressed in this country. Our history is often solely defined as us being slaves. But it’s important to note that as slaves, we actually were the underlying assets to many institutions we have today.

Did you know slaves were the initial deposits for farms and banks and other institutions that are still standing that were owned by slave holders? The irony of our ability to be assets but not asset holders is absolutely absurd. As I think back on the history of the African-American people in this country, I am thankful to Freedman’s Bank and now City First Broadway, because I do truly look forward to the day when we can reclaim our economic value in society.

Credits:

- Founder Hustle and the Deep Cut are produced by Kinetic Energy Entertainment

- Edited and mixed by Ann Kane.

- Social media producer is Misako Envela

- Music is Ratata by Curtis Cole